When the Answer Is More Than then Sum Of Its Parts

Albert Einstein was one of the greatest minds of the 20th century, and along with probing the mathematic underpinnings of the universe he was known for several inspiring quotes. My personal favorite Einstein quote is, " "I never said even half the things that the Internet says I did."

Wait, that's not right. I meant the other one, "If you can't explain a concept to a six year old, you don't actually understand it yourself."

Whether Einstein actually said that or not, it's a deep quote with a lot of different layers. And it perfectly covers today's topic, namely the unexplained software errors plaguing Minnesota's latest breath test machine. You can read that blog for more information, but the short version is "the machine appears to measure breath samples just fine, but then prints out results that are different than what it actually measured."

This issue is something that we've been working on, in-office and behind the scenes, for years. And in the last few months we've wrapped up our efforts and started using what we learned on behalf of our DWI clients. When we won the first case on behalf of a client, we shared the result on our blog, along with a redacted copy of the court's order.

We then immediately started fielding calls from the media, calls from the public, and calls from other defense attorneys. The defense attorneys in particular all had the same question, and tellingly, it wasn't "how did you do it?" No, the question we kept getting was "what exhibits did you use?"

The assumption here is that because the judge's winning order was so favorable, and so easy to read, that any defense attorney should be able to just jump in (with the right documents) and get a similar win for their clients. But that's just not true, or even possible, and here's why.

All those years of work, discovery requests, Minnesota Data Practices Act Demands, visits to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, all provided the basis for uncovering these errors. It took even longer to be able to formulate what we discovered in a way that we could "explain to a six year old." That's not me equating any judge to a six year old; that's just a poetic way of pointing out that judges are expected to know every law, and simply can't be expected to also be in-depth experts on every single type of forensic scientific evidence. We saw a glaring error in Minnesota's DWI breath testing program, and needed to be able to explain it in a concise yet accurate way.

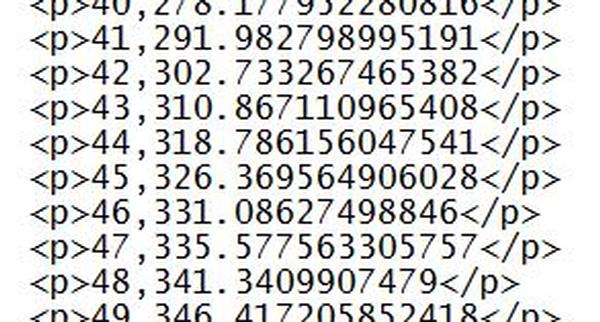

The why is so very much more important than the how when it comes to this type of scientific challenge. If you want to know the how, as in "what exhibit do I need to use," just click this link right here. That's what we got from the BCA. If you're too lazy to click (or don't trust downloads from the internet, which is actually a pretty smart policy) here's a small sample:

That's what we used to win this case, and what we intend to use to win future cases. That's the "how."

But taking that, and using it in a way that makes sense, is nothing that can be easily explained in a five minute conversation, or even a five hour conversation. That's partly due to the complexity of several different scientific differences, and partly due to the fact that the Minnesota BCA has a terrible track record of owning up to mistakes, and show every intention of fighting these errors to the bitter end -- meaning every court case is going to be a bloody, messy battle where the attorneys need to know as least as much as the experts.

So here's the wrap up: we've always gone out of our way to share our discoveries with the defense bar, and are going to continue to do so. We've been teaching seminars for years regarding breath testing in general, and more specifically on topics like measurement uncertainty, systematic bias, and statistics . . . because all of those topics are now required reading to defend many DWI breath tests.

We've also been hired as consultants on a variety of those cases, and will continue to offer our services as consultants in new cases where these new challenges may come into play. That's not a cash grab (most people understand that there are far more lucrative areas of law than criminal defense work), it's simply the only way to properly present complex arguments. As many of the attorneys who previously hired us as consultants can testify to, once you've worked alongside us for one case, everything makes more sense and you are very close to be being able to raise these issues completely on your own.

Nothing teaches more effectively than doing. So if you want to help us in our never-ending quest to prevent garbage science from leading to wrongful convictions, don't ask us "how." Instead, get ready to learn "why."