"Consent" in the Wake of State v. Brooks

Right now in Minnesota, courts' interpretation of DWI law is all over the map â?? the law is uncertain, with more gray areas and questions than black-and-white answers.

Is "consent" to search relevant in the DWI context in Minnesota?

Is actual consent possible when "consent" is implied by law?

Do drivers have a "right" to refuse a test when exercising that "right" is a crime (test refusal)?

Does the Fourth Amendment even apply to DWI searches in Minnesota?

Currently, once a driver has been arrested for DWI in Minnesota there are only two possible outcomes: submit to a warrantless search (blood, breath, or urine), or get charged with a crime for refusing to submit. There doesn't seem to be much consent involved. And this appears to apply not only to drivers who have consumed alcohol; the same take-the-test-or-break-the-law "choice" must also be made by drivers who are simply driving while taking medication as prescribed.

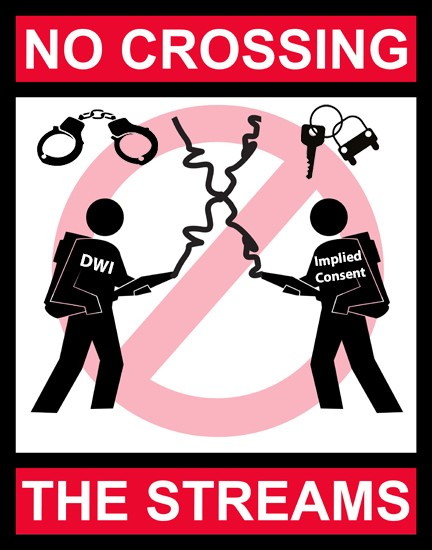

We weren't kidding when we said there are more questions than answers. We depend on judges to come up with the answers, but we can certainly pinpoint the source of all the questions and confusion: the legal fiction that our Implied Consent Law (which governs license revocations) and DWI law (which puts drivers in jail) are separate from each other.

The Minnesota legislature has decidedâ??under the Implied Consent Lawâ??that in exchange for their driving privileges, all drivers arrested for DWI impliedly "consent| to submit to a warrantless search (chemical test of blood, breath, or urine). If a driver refuses to take a test, or if the driver takes and "fails" the test (.08 or higher), the State takes away the driver's license.

The legislature has also decidedâ??under the DWI statuteâ??that driving with an alcohol concentration of .08 or higher is a criminal offense punishable by jail time.

The problem is that the legislature |crossed the streams| of the DWI and Implied Consent laws when it made it a crime, under the DWI law, to refuse to take a test under the Implied Consent Law. Together, the laws make it illegal for an arrested individual to refuse to submit to a warrantless search for criminal evidence.

This is a classic Catch-22 for the driver. By claiming the laws are still separate, the state is able to use a driver's implied consent to take a chemical test (in exchange for a driver's license) simultaneously as irrevocable "consent" to a warrantless search for criminal evidence.

Now, we aren't judges, but in our opinion this seems unconstitutional, for several reasons. First and foremost among them being the fact that |consent,| by definition, is permission freely and voluntarily given. Permission can always be withdrawn. If permission can't be withdrawn (without incurring criminal penalty), it's not voluntary, and therefore, it's not consent.

It wasn't that long ago that Minnesota judges agreed with us:

|The obvious and intended effect of the implied-consent law is to coerce the driver suspected of driving under the influence into â??consenting' to chemical testing, thereby allowing scientific evidence of his blood-alcohol content to be used against him in a subsequent prosecution for that offense[,]| Prideaux v. Minnesota, 1976, and "[a]n officer has a right to ask to search and an individual has a right to say no.| State v. George, 1997.

However, since 2013, in Missouri v. McNeely, when the United States Supreme Court clarified that the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement does indeed apply to DWI tests (again, blood, breath, and urine), Minnesota courts have issued a series of contradictory decisions â?? and there doesn't appear to be any end in sight.

For instance, in State v. Brooks (2013), the Minnesota Supreme Court noted that |[t]he Minnesota Legislature has given those who drive on Minnesota roads a right to refuse the chemical test[,]| and |by reading the implied consent advisory police made clear to [the driver] that he had a choice of whether to submit to testing.|

But this analysis depends on the legal fiction that the implied consent and DWI laws are separate. The statutory reality is that under the DWI statute, |[i]t is a crime for any person to refuse to submit to a chemical test of the person's blood, breath, or urine under [the Implied Consent Law]," even though the Implied Consent Law says that |[i]f a person refuses to permit a test, then a test must not be given.|

Can a single act, such as test refusal, be both a right and a crime at the same time?

Confused?

Wanna know our answer?

GET A WARRANT.

DWI suspects have the same constitutional rights as everyone else.

1. Collection and chemical testing of blood, breath, and urine are searches under the Fourth Amendment that require a warrant or consent;

2. Submission to a chemical test required by law, in order to avoid committing a crime by refusing to submit, is not consent; and

3. It is unconstitutional to criminalize refusal to submit to a warrantless search.

But we aren't judges, and according to case law, it appears that consent just isn't relevant in a post-Brooks world.

There is hope on the horizon . . . We expect to see new developments in this area from our federal courts in the near future. Stay tuned â?? it may be a while before the fog clears, but we'll be here to help you navigate DWI law until it does.

This is the third post in our blog series, Consent as an Exception to the Fourth Amendment Warrant Requirement: DWI Alcohol Testing. In this series we discuss:

1. The History of the Consent Exception to the Fourth Amendment Warrant Requirement

2. The Evolution of the Consent Search Doctrine

3. Minnesota's New Standard for the Consent Exception to the Fourth Amendment: State v. Brooks

4. Consent as a Matter of Law: The Minnesota Court of Appeals and the Consent Exception to the Fourth Amendment

5. The Constitutional Implications of Minnesota's New Standard for the Consent Exception to the Fourth Amendment

6. The Future of the Consent Search Doctrine